About Bach’s Canon

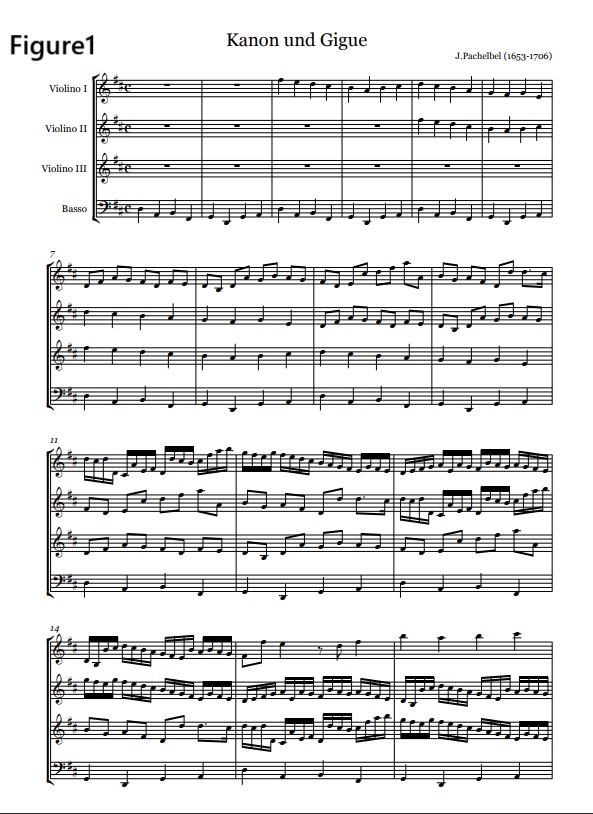

When you hear the word “canon,” what comes to mind? Probably 90% of people think of “Pachelbel’s Canon” (Figure 1). However, you might be surprised to learn that Pachelbel’s Canon isn’t actually a canon. Yes, Pachelbel’s Canon is more appropriately called a “variation” than a canon. Since the three voices develop in a “canon-like” manner over a basso ostenato, it’s fair to say it’s a “canon”, but it’s undoubtedly an extremely “easy-made” canon. A similar work is Henry Purcell’s “Chaconne (from Dioclesian)”.

Now, I’d like to explain what a “true canon” is. First, I must say that a “canon” is not the kind of music that just any composer can create. Telemann wrote “12 Canon Sonatas for Two Flutes”, which I think are exceptionally well-crafted pieces of this type. However, if you were to ask who the greatest composer of canons is, it would have to be Johann Sebastian Bach.

The first one that comes to mind is the “Goldberg Variations”. Nine of these variations are canons. The canons are set in every third variations, beginning with a canon of the same degree, then gradually increasing in intervals of a second, a third, and finally a ninth. What makes this Bach piece miraculous is that they are all written on the same bass note (harmony). If you’re wondering, “Isn’t that the same for Pachelbel?”, remember that Pachelbel’s canon is “simply” a two-bar basso continuo repeated over a dozen times. In contrast, Bach’s piece develops the canon from a first to a ninth over 32 bars of bass notes, without any musical contradiction. Its musical “structural beauty” is truly “worlds apart” from Pachelbel’s.

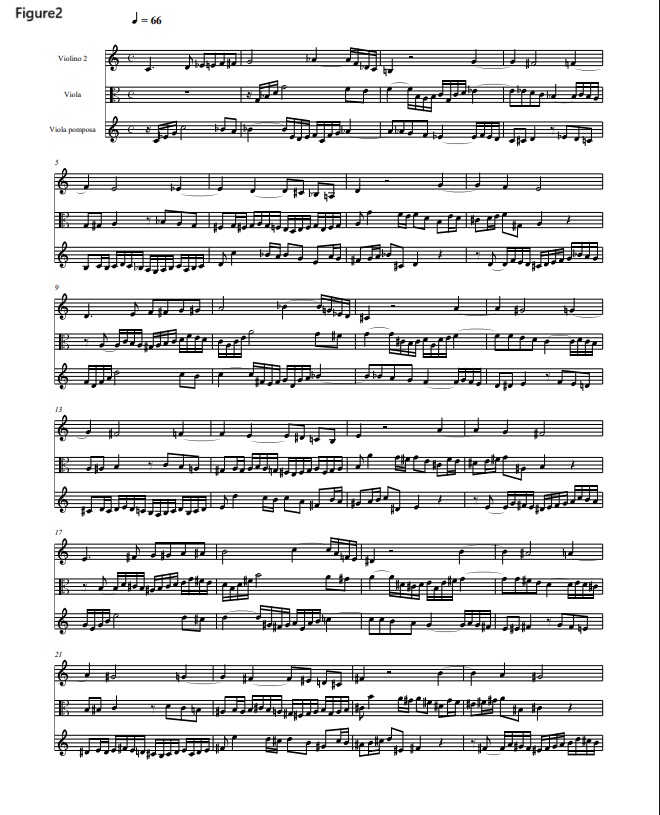

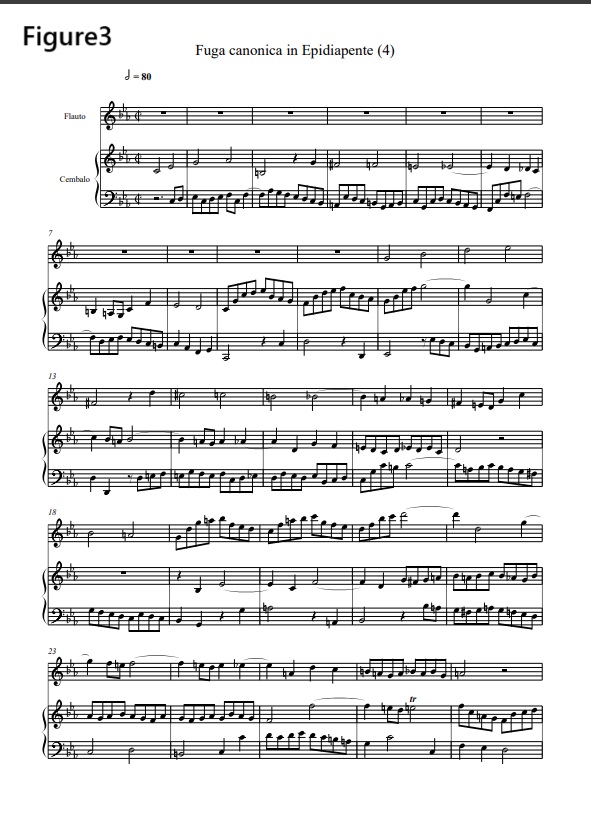

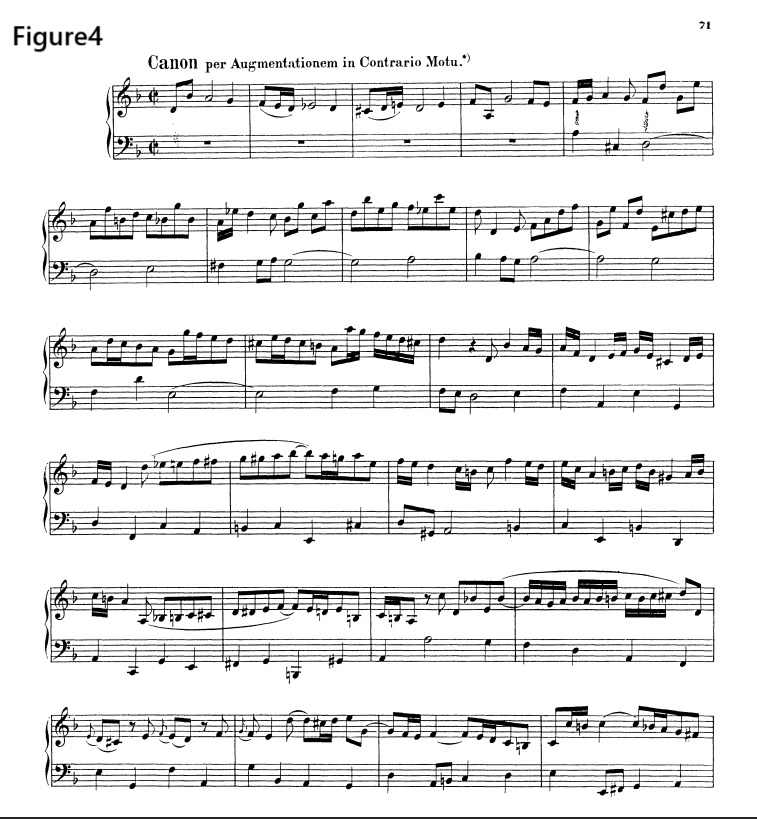

As you probably know, in addition to this type of canon, Bach also left behind just about every conceivable canon. Famous examples include “The Musical Offering” and “The Art of the Fugue”. In the former, Bach consistently combines a theme from Frederick the Great with canons of amplified, Expanded Canon, Inversion (Mirror) Canon, Retrograde (Crab) Canon. In the “Ascending Canon” of No. 5 in particular, the theme ascends while modulating the C minor scale over an octave, finally returning to C minor—a miraculous feat (Figure 2). Another example is the Fugue Canonica in Fifths, in which a fugal fifth responds with a fifth, while at the same time the upper two voices become a canon—a work that could be called the magic of modulation (Figure 3). In “The Art of the Fugue”, there is a canon in which the second theme is expanded and furthermore Inversion (Figure 4).

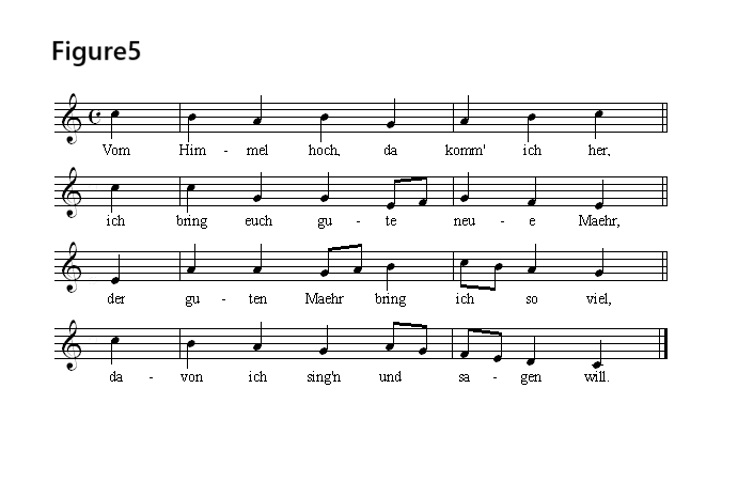

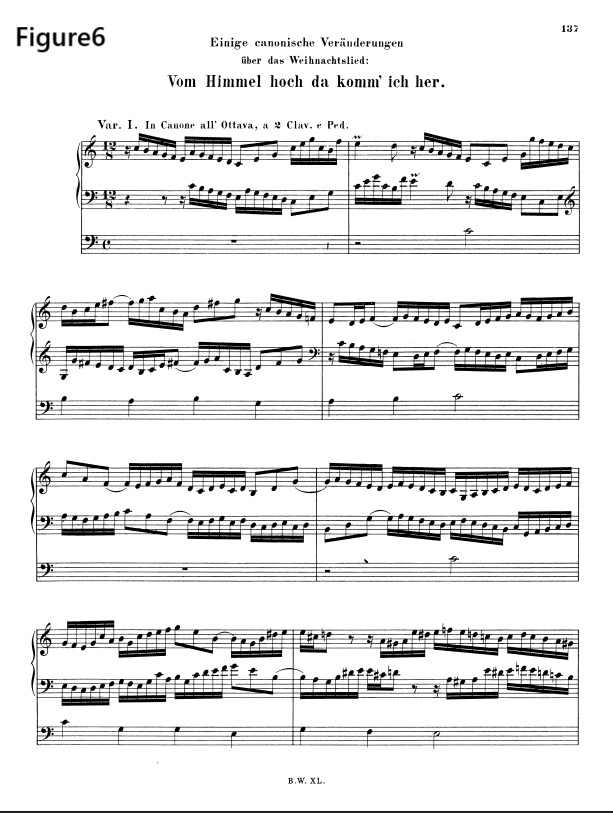

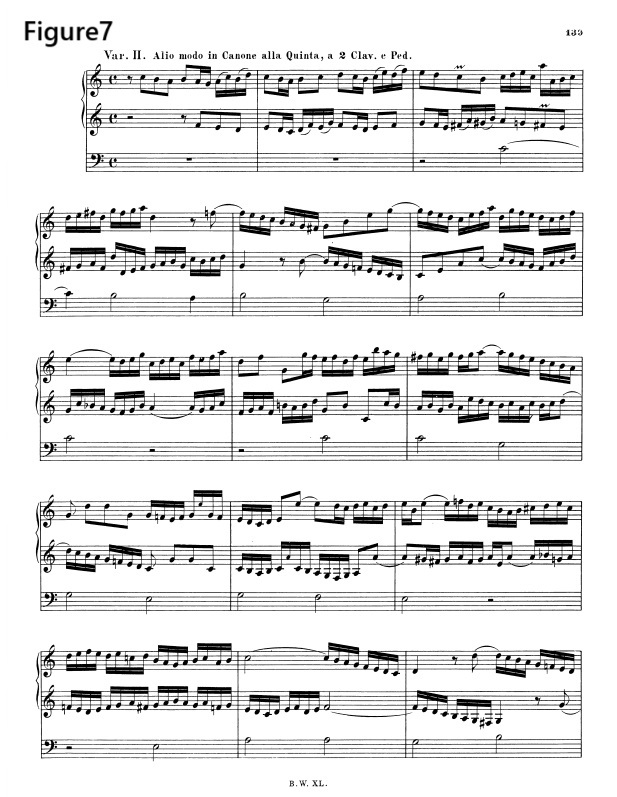

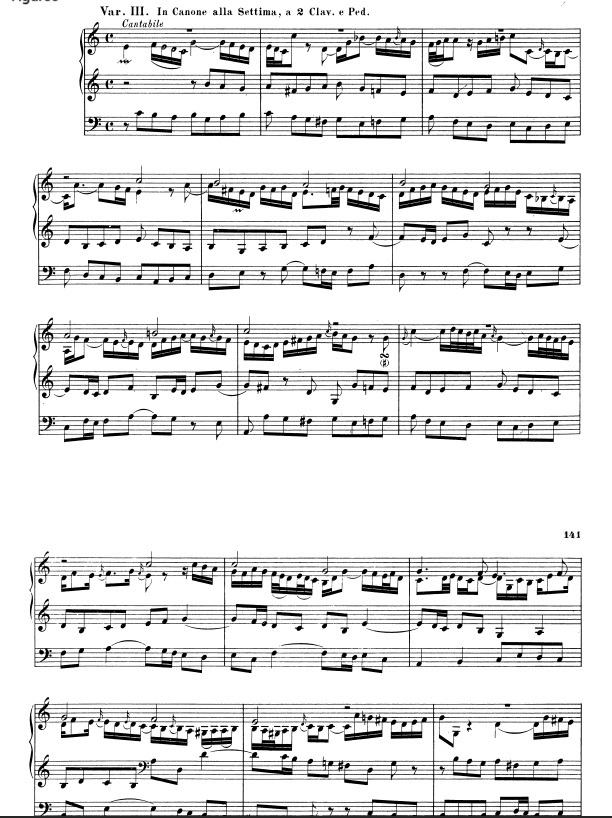

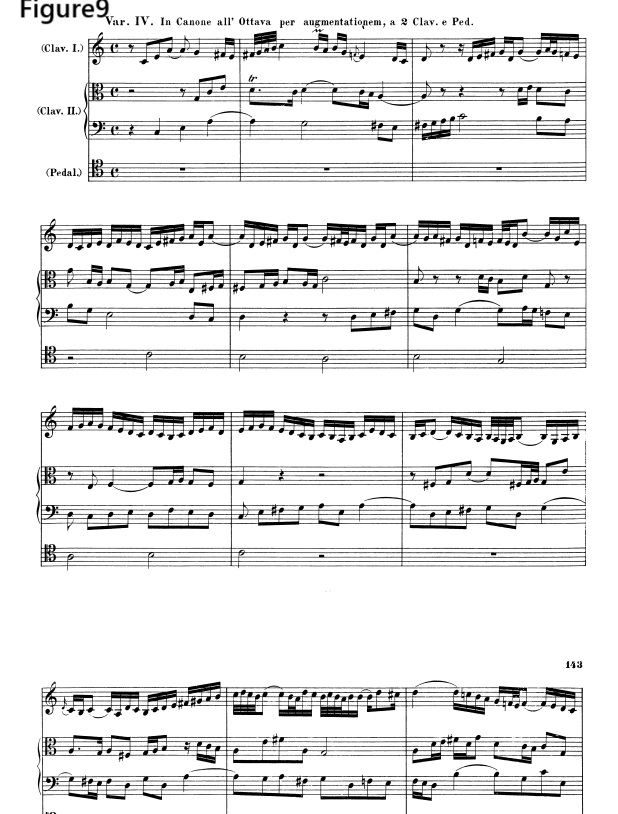

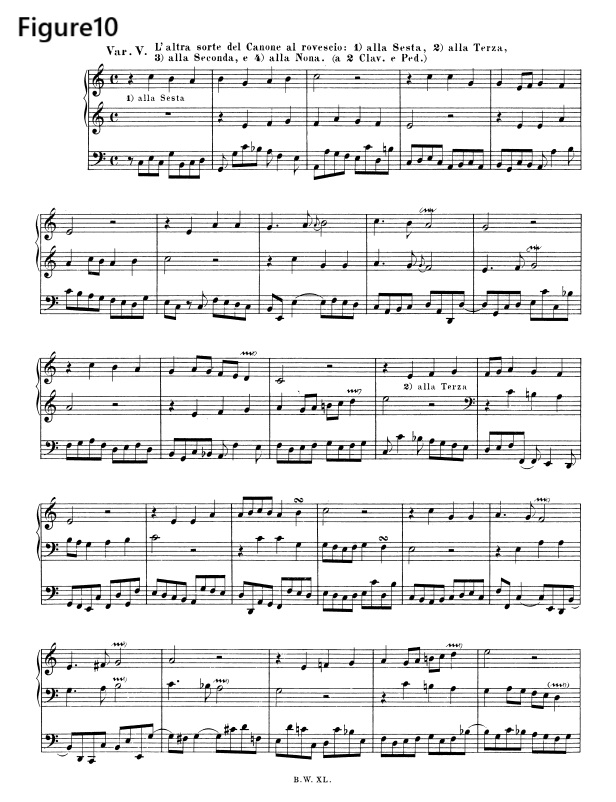

Let’s take a look at the Canon Variations for Organ, BWV 769 (“Vom Himmel hoch da komm’ ich her”), originally a chorale by Martin Luther (Figure 5). Of the five movements, the first and second feature a canon (octave, fifth) played by the manuals, accompanied by a chorale melody played by the pedal (Figures 6 and 7). In particular, the second movement’s canon theme is also derived from a chorale melody. In the third movement, the left hand and pedal play a chorale melody reduced to eighth notes in a seventh canon, while the right hand plays a free melody and a chorale melody of longer note values, for a total of four voices (Figure8). In the fourth movement, the bass on the left hand follows the melody in the right hand, an octave lower and with double-length notes. While the left hand plays a more independent part, the pedal plays a chorale melody (Figure 9). It’s probably no coincidence that a subtle eighth-note “BACH” motif is inserted three measures from the end. In the fifth movement, the chorale melody itself is treated as a canon (the soprano plays the chorale and the alto plays the inversion) (Figure 10). In the second half of the movement, the soprano is given a free melody, and the pedal chorale and the tenor (inversion) play the canon in quarter notes. The free melody is then passed on to the tenor, who, after a soprano chorale and pedal inversion, concludes with a pedal cadenza, organpoint, and a stretta for all voices, resulting in a solid six-voices coda. #baroque #bach #canon #片山俊幸